IN THIS ISSUE

- News from Ireland

- Fields of Rye by Mattie Lennon

- A Penny Icecream and the Smell of Creosote By Mattie Lennon

- Which Island Prison by Dan Allsopp

- Gaelic Phrases of the Month

- Monthly Free Competition Result

Popular Articles from Recent Newsletters:

FOREWORD

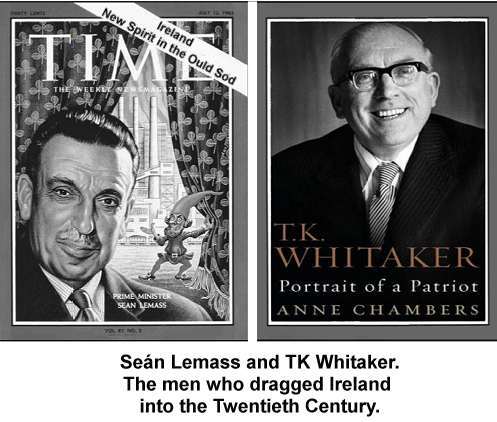

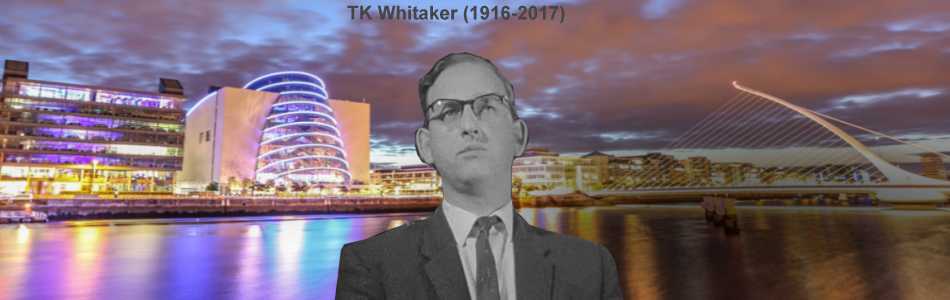

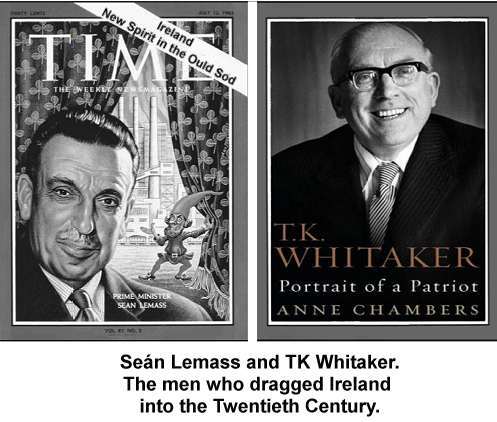

The death has occurred of the man voted as 'the greatest living Irishman' and the 'Irishman of the Twentieth Century'. TK Whitaker truly had a remarkable career and life and while there are countless Irish people who are not familiar with his work a review of his legacy (see the news article below) confirms his status as one of the most important Irish people of modern history.

This month we also have another fine story of Ireland of yester-year from Mattie Lennon.

If you have a story or article you would like to contribute please do send it in!

Until next month,

Michael

P.S.

Please Do Forward this Newsletter to a

friend or relative. If you have a website or Facebook

page or Blog (or whatever!) then you can help

us out by putting a link on it to our website:

www.ireland-information.com

|

NEWS FROM IRELAND

DEATH OF THE LEGENDARY TK WHITAKER

'A National Treasure'

'One of the Architects of Modern Ireland'

'As fine an Irishman as there has been'

The plaudits continue to arrive in tribute to TK Whitaker who was easily the most influential civil servant in the history of the Irish State.

The former Secretary of the Department of Finance also served as Governor of the Central Bank, but will perhaps be most remembered as one of the driving forces behind the 'First Program for Economic Expansion' from 1958 to 1963.

Ireland of the 1950's was a very backward place. The declaration of an Irish Republic in 1948 had not brought a major improvement in the standard of living from that experienced under British rule. The memory of the bitter Irish Civil War ensured that the those in favor of and opposed to the 'Anglo-Irish Treaty' of 1922 remained suspicious of and divided from their fellow countrymen and women.

Ireland had remained neutral during the second World War, and was to pay a price economically and psychologically for this stance, as the country remained somewhat excluded from the realm of European nations.

When Sean Lemass became Taoiseach in 1959 he found in TK Whitaker a like-minded progressive who was determined to get something done and who had as early as 1957 compiled his document outlining his economic proposals. Together they implemented the economic plan that included a major switch from protectionist policies to those of a free market, with Lemass significantly signing the GATT (General Agreement on Taxes and Tariffs) in 1960.

Ireland then joined the European Free Trade Association while the IDA (Industtrial Development Authority), was expanded and tasked with attracting foreign direct investment into Ireland, proving to be a remarkable success over the last half century.

Antiquated policies such as the 1932 'Control of Manufacturers Act' were removed. This legislation required that any Companies established in Ireland had to be at least partially Irish-owned. Lemass and Whitaker saw this as a barrier to free trade and removed it.

Grants to Irish farmers and businesses to enable them to modernize were made available.

Regional Technical Colleges were established, (several of which are now making the transition to full University status).

Free Child Benefit payments were introduced in 1963 and free secondary school education in 1969.

Lemass also looked to Britain and in 1965 signed the 'Anglo-Irish Free Trade Area Agreement' that abolished tariffs between Ireland and the UK, an agreement that was to have tremendous economic benefit for Ireland. And one which is now facing a degree of uncertainty in the face of Brexit.

The results of these economic changes were staggering.

By the end of the program Irish exports had risen by a massive 35%.

Emigration between 1956 and 1961 had seen 212,000 leave Ireland, a truly massive number. But from 1962 to 1967 80,000 emigrated from Ireland and while still a huge number is one that is obviously very significantly reduced.

Ireland had finally been modernized with the transition from backward near-third-world economy into one that could look forward to EEC (forerunner of the EU) membership and taking its place among the developed world states.

TK Whitaker had been at the very heart of this change with his near-revolutionary vision for economic change being championed by the willing Sean Lemass.

He also served as Chancellor of the National University of Ireland from 1976 to 1996 and in Seanad Eireann from 1977 to 1981. He was President of the Royal Irish Academy and a member of the board of the National Gallery of Ireland.

He had married Nora Fogarty in 1941 with whom he had six children and after her death in 1994 married Mary Moore in 2005. He died a month after his 100th birthday.

TK Whitaker was conferred with the title of 'Irishman of the 20th Century' in a public vote in 2001, such was his enduring influence over the lives of the Irish people.

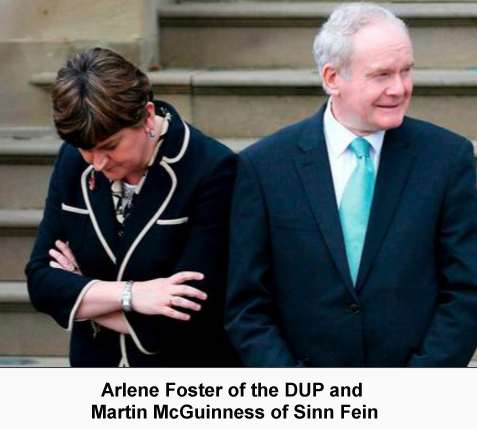

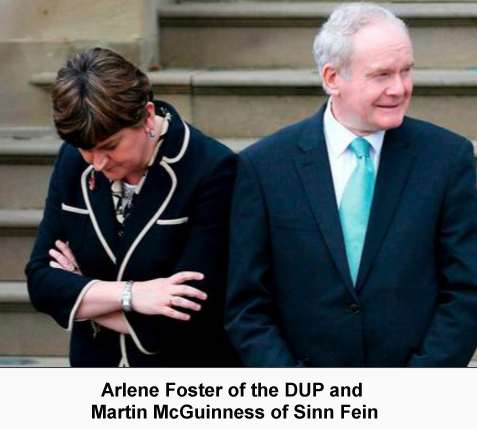

NORTHERN IRELAND POLITICS IN TURMOIL

The sudden resignation by Sinn Fein Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness has put the spotlight back onto the difficulties being faced in Ulster.

Already reeling from the 'Brexit' vote (the Province voted to stay within the EU) that could see the six Counties wrenched from the European Union against its will, the Northern Ireland Assembly (Government) has been further rocked by the so-called 'cash for ash' scandal.

The 'cash for ash' scheme is a 'Green Energy' scheme that looks set to cost over £490 Million, (about 563 Million Euro). The way the scheme was set up meant that for every £1.15 participants paid for fuel they were then reimbursed with £1.65 in subsidies. It has been speculated that many participants over-spent on and wasted fuel in an effort to maximize their profits.

Sinn Fein had called for the DUP (Unionist) First Minister Arlene Foster to temporarily step down to allow an independent enquiry into the matter. She refused so McGuinness resigned, likely signalling the need for an Election and the collapse of the Assembly in Ulster at this most difficult of economic and political moments.

|

KEEP THIS NEWSLETTER ALIVE!

FIND YOUR NAME IN OUR

GALLERY OF IRISH COATS OF ARMS

|

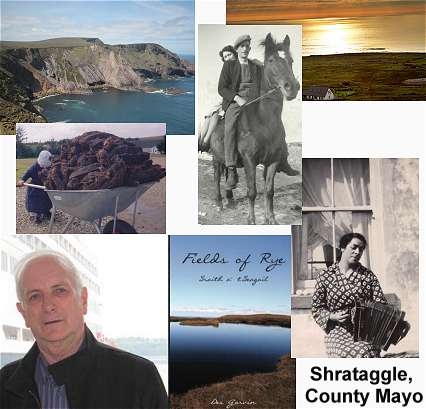

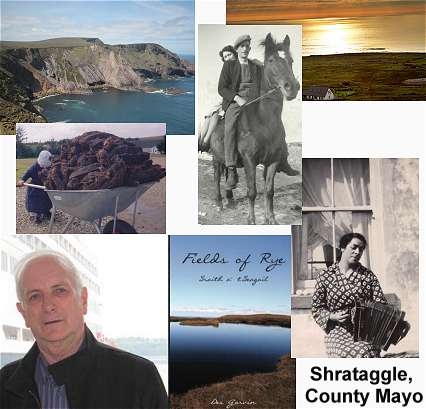

FIELDS OF RYE

by Mattie Lennon

Des Garvin was born and reared in the townland of Shrataggle, County Mayo.In his recently published book 'Fields of Rye”, he uses Shrataggle as a blackboard to illustrate life in all of rural Ireland in the last century and before.

Traditional music was always one of his passions and he has been a leading light in Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireannn for many decades. Involved in Peace Groups in Northern Ireland for thirty years his leadership ability became evident as a young teenager.

When Rural Electrification was introduced to his native heath the Ground Rents proposed by the ESB was exorbitant. He tells us,

'...the ground rent on our house was calculated at 15 Pounds and that was payable every two months. Today, that is roughly the equivalent of 290 Euro, and it was extortion plain and simple.'

It was highly unlikely that any of Des's neighbours would sign up. Out of economic necessity there were forced to say no. Tony Blair said that the art of leadership is to say no but Des wouldn't agree.

The young boy from Strataggle convinced all and sundry to say 'yes' despite the outrageous price quoted,

'..at least until the lines arrived in the village.'

The result? The ESB was left with no choice but to join the village to the network. As luck would have it, between the beginning of the project and the houses of Shrataggle being connected, the government of the day introduced a subsidy which reduced the ground rent to 2 pounds every two months.

The island of Inishlyre, in Clew Bay, County Mayo, was only connected to the national grid in September 2000. Obviously they didn't ever have a young Des Garvin living there!

An in-depth genealogical analysis of Garvins, O'Malleys, Cormacks, Gilroys and every other family that inhabited Des's part of Mayo for centuries is a collector's item. A photo gallery of 157 images contains pictures – including 'The Bridge at Sharaggle' and 'Last Rick of Hay'- that would, otherwise, have been lost, are now moments frozen in time and recorded for posterity.

97 year-old Catherine Garvin, from Shrataggle, has been living in New York since 1939. She educated herself and had a very successful career in the travel trade and later the legal and banking business. She was one of 40 travel agents on board, in April 1958, when Aer Lingus introduced its trans-Atlantic service with the Seaboard Super Constellation.

A few months ago Des interviewed her for his book. She told him of how she attended secretarial school after arriving in New York and became proficient in shorthand and typing. And... whether cutting turf in Mullach Padda Bhain or negotiating with people who were key figures in the Good Friday agreement, Des Garvin would leave no stone unturned. He gave the Shrataggle nonagenarian a sentence and asked her to reproduce it in Pitman shorthand.

She produced the result '...in moments.'

The author doesn't go overboard in blowing the trumpet of his own family. Although he does point out that his aunt Anne, who worked as a cook in the Royal Victoria Club in Leeds, was responsible for introducing chips and Yorkshire pudding to Shrataggle.

Some years ago Councillor Joe Mellett said of John Healy, that other great writer from Mayo:

'He's a guy that we can associate with especially in bad times. He made the rest of the country aware of what was happening then.'

The comment also describes Des Garvin.

Wren-boys, Cillins, Missioners, blasting with gelignite, illicit distilling and travelling shows feature. It's all there in the book.

In my working days Des was my boss for a number of years and am I glad that I didn't ever cross swords with him. What would be the point of taking on somebody who, when barely out of short trousers, convinced a stubborn rural community to take action against a Semi-State body that would result in an 87% reduction in ground rents?

Details of 'Fields of Rye' can be found at:www.shrataggle.com

|

A PENNY ICECREAM AND THE SMELL OF CREOSOTE

By Mattie Lennon

It was Christmas morning 1952. I was being let by the hand to early Mass in Lacken.

Why did my mother have me by the hand since, in the words of Patrick Kavanagh, I was 'six Christmases of age'? It was partly because my mother considered me 'wild' - although in later life I would always claim that I was an eejit but didn't tick any of the boxes that would constitute 'wild'.

The valley was in darkness save for the candles in the windows to welcome the Redeemer. It was a scene that wouldn't ever be repeated.

Rural electrification was just arriving in Lacken and the surrounding area but had not yet been switched on. Post- dawn it would be possible to see poles which had stood, complete with insulators, all summer, sentry-like across the countryside and now strung with high-tension cables. An ESB official, one Mr Heevy from Naas, had called to the school to complain about the number of insulators which had been the victim of stone-throwing. The schoolboys from the townland of Ballinastockan were the prime suspects. Not because they were more destructive than the rest of us but they were young marksmen with a stone or any small missile.

If you stood close to an ESB pole and looked up it appeared to be falling, something to do with an illusion caused by the rolling clouds. The term 'optokinetic movement 'would have meant very little the First Communion class of 1952.

Not every house opted for the ''lectric light'. This was mainly out of economic necessity and the 'cups' on the chimney became somewhat of a status symbol. The switching-on ceremony would be performed in The Parish Hall, Valleymount, in January 1953 but for now the valley's illumination was confined to candles, oil-lamps and the wick-in–a-Bovril-bottle source of illumination known as a 'Jack-lamp'.

Adult Mass-goers spoke of the well-dressed men in Ford vans who were travelling the district selling everything from electric irons, to electric kettles to electric fires.

Conversation in the area was dominated by several fanciful theories. Boiling water in an electric kettle 'takes all the oxygen out of it'. There was also a story about a cat being electrocuted (I heard the word 'executed' used). In the smoke-filled cabins of west Wicklow it was believed that you couldn't wash a light bulb. And then of course somebody came up with the stupid riddle: 'How does a one-armed man change a light-bulb?'. 'He keeps the receipt'.

The fact that improved illumination would highlight physical defect was not overlooked. It was rumoured that one elderly farmer who had two daughters of marriageable age but not blessed with film-star looks was heard to say, 'we'd better get rid of thim two wans before the 'lectric light comes.'

One night when such matters were being discussed in a rambling-house Jack Farrell was sitting in the corner. Jack was a Tallaght man who had inherited a small cottage in the area. There were those who would insist that not all of Jack's stories ran parallel with the highest ideals of veracity. Anyway Jack related the following story.

Jack's father ,farmed in Killenarden (it was at the back of Jobstown... and still is). He went for the pension and was asked if he remembered 'the Big Wind'. The Big Wind was on 6th January in 1839 so if Jack's father remembered it that would leave him over 70 in 1908.

Farrell senior was more than equal to the challenge. According to Jack his father told the pension officer that, on Sunday sixth of January 1839 he was sitting at the fire when a squall of wind took the roof straight off the house and it landed somewhere about Kippure. A pot of potatoes that was hanging on the pot-rack was blown up the chimney and at the top wasn't it struck by lightning. The steam that came out of it was a fright to the world and, says Jack:

'They were the first potatoes in Ireland to be boiled by electricity'.

The specified depth for the main-line poles was six foot two inches. Local men were employed as labourers and Neddy Cullen, who was vertically challenged (it was said of him that he could play hurling under a bed) was digging a hole in Tim Browe's field. When he was standing in the hole head and shoulders above the ground he uttered the immortal words: 'If that hole is not six feet deep my name is not Neddy Cullen.'

When the lorry loads of poles began to arrive it was the first time that I had smelled creosote. When they were hoisted by a number of men it was ensured that each pole was parallel with the perpendicular. In the pre-digital age this was achieved with a length of string and a suitable, small, piece of Wicklow granite serving as a plumb-bob.

As children we re-enacted everything that we saw the 'wire men' doing during the day. We were digging holes for 'poles' and taking our mothers' spools of thread to string 'wires.'

I recently saw a cartoon depicting a person of my age with the caption, 'I've become so forgetful that I can now play my own surprise parties.' I understood but I can vividly remember the writing on the first, yellow, warning sign that I saw on an ESB pole sixty four years ago:

DANGER

Keep away.

It is dangerous to touch the electric wires.

Beware of fallen wires.

My old school mate, Pat Brennan, brought the 'lectric light' out to the shed and the pig-sty using wire from a bed spring. You'd be talking about health and safety! When we were both aged under ten years of age Pat showed me how to by-pass a meter and twenty years later when I was living in a flat in Ranelagh...

No ordinary household would dream of buying a fridge and for me, and the twenty-seven, other juniors in the 'little School' it was a day to be remembered when Mrs. White brought in a tray from Burke's shop bearing twenty-eight penny ice-creams.

Nocturnal radiance, and a single round three-pin socket was the limit for most houses but electricity broadened the cultural horizons of the community. When Julia Carroll who had spent a lifetime in New York returned for a holiday her husband, Harry Wenkee, was able to show pictures in the local school. And a travelling (called a 'fit-up') show came to Brennan's field.

For most of us youngsters it was out first experience of stage-shows. Singing, dancing and drama meant entertainment for all. Plays such as 'Murder in the Red Barn' mesmerised us rural innocents. Conjuring was, to us, 'pure magic' but the boss of the outfit, Jackie Ellis, was the best hypnotist I have ever seen. Audience participation in his act brought the house down. One of my schoolmates was asked by Mr. Ellis to sit on an ordinary kitchen chair. When his posterior touched the seat he jumped; the chair was 'red-hot.'

The appearance of a fit-up in the area after so many years triggered reminisces among the older males. They spoke of a travelling show which visited the district and set up in the 'quarry-hole' in Ballinastockan in the early days of the century. There would be sly grins when a male septuagenarian would make reference to 'Tilly.' A showgirl from the quarry-hole in the dim and distant past. Even at age 11 I gathered from the nudge, nudge, wink, wink, flavour of the talk that Tilly was in the habit of exposing more than her ankle.

In the 40s and 50s a resident of Lacken or Ballinastockan carrying an acid-battery, (I believe the correct term was an accumulator), to Blessington to be charged was a familiar sight. Electric wirelesses gradually took over and by the late '50s a large carboy surrounded by straw in a wicker basket in Johnny Kelly's garage was the only remaining relic of the old battery wireless.

About the memories evoked by the olfactory sense, Marcel Proust, in The Remembrance of Things Past, has put it much better than I can:

When nothing else subsists from the past, after the people are dead, after the things are scattered... the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls... bearing resiliently, on tiny and almost impalpable drops of their essence, the immense edifice of memory".

Now, when a neighbour is treating his garden fence and the smell of creosote wafts on the summer air. It is no longer the 21st century. I don't have the free travel. It's 1952 and I am, once again, a six-year old in Kylebeg.

|

Which Island Prison

by Dan Allsopp

Ireland and Australia, in the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, with respect to the Irish people's way of life, certainly had their differences, but also had many similarities, yet each ventured down different paths towards their future.

Ireland was under the British yoke and had been for centuries; Australia started as a penal colony for the British but, the Irish people progressed and many prospered in a different way for their home country. Was one country more oppressed or imprisoned than the other?

A comparison of Irish people in each country will follow by referring for the most part, to two extraordinarily well written and researched books: The Story of the Irish Race by Seamus MacManus and The Irish in Australia by Patrick O'Farrell.

MacManus refers to Professor Lecky who points out that the various Penal Laws imposed on Ireland by Britain from the 1600s to the 1800s were so oppressive to the Catholics in Ireland they may as well have added the words 'To extirpate the Race', meaning all the Irish and 'the degradation of a nation' (p.454).

However, Gaelic culture was not dead and its language would find its way to Australia and continue for a short time among the convicts yet, and St Patrick's Day endured. O'Farrell quotes an analysis of literacy skills between 1817-39 in New South Wales, where it was revealed that Irish convicts in England were not very different to English convicts (p.26).

For any Irish person in Australia, speaking English would prove to be advantageous. Gaelic would often be viewed as untrustworthy or plotting; to speak English, they are 'conquering the language of the conquerors' (p.27).

It was Captain Cook's detailed exploration and mapping of the eastern coast of Australia in 1770, which he called New Wales (as opposed to New Holland), and his reports that struck appeal to the British government as a place that could be utilised. With the loss to America in their War of Independence and a place to send convicts, together with overcrowded prisons in England, New Wales had appeal.

It could provide timber, a whaling base, discourage French exploration and serve as a place to off-load convicts. From the First Fleet arriving in Sydney Harbour in January 1788 to the Second Fleet the following year, O'Farrell points out that of the convicts, crew, officers and guards, all included Irish (p.22).

New Wales was regarded as so remote that, if the convicts improved and rehabilitated, then better still. Australia had ample land and little labour, Ireland was the opposite. To survive in Australia, adjustments had to be made, including cultural. In time, these Australian-Irish grew potatoes because they knew how to and there was a market for them. Even with this in mind, O'Farrell refers to a Peter Cunningham in 1825 who points out the different groups among the convicts: Cork Boys, Dublin Boys, Northern Boys. Tipperary provided the most convicts (p.28).

In Ireland, MacManus points out that regarding the Suppression of Irish Trade, 'there was no parallel in history' which goes back to the 14th Century (p.483). He again quotes Lecky in that it was to 'blast the prosperity of a nation' (p.492).

O'Farrell, however, makes an important observation in his introduction as to who were the Irish in Australia? He includes Gaelic Catholic, Anglo Irish, Ulster Protestants, Irish Jews, Irish Quakers all coming from different parts of Ireland over time. In fact, as time went by, an Australian stereotype was a tanned bushman, digger, lifesaver (on the beaches), with the combined Irish contribution to independence, lawlessness, anti-authority, generosity, liking a drink and being as game as the notorious (yet idolised) bushranger, Ned Kelly.

MacManus pointed out that while the British squashed countless attempts by the Irish to shake off their British overlordship, the Irish spirit was never actually killed off, even from the time of Cromwell through to the 1900s. In fact, many Irish convicts in Australia escaped, most caught again, but then were allowed to become explorers merely to point out that there was no way home.

Many thought there was a way to China and freedom, but were ridiculed for their ignorance. However, the last lot of Irish convicts that arrived in Western Australia in 1868 included many Fenians and one fellow, John Boyle O'Reilly, who escaped and went to America the next year. In 1876, American Fenians rescued six convicts from Western Australia and made it back to America; why America? Because It represented freedom.

Yet, despite the appealing qualities of the Irish-Australian persona, there is a deeper side. O'Farrell raises the perception of the Irish-Australian convicts as 'honourable victims' of injustice, oppression or heroic rebels (p.23). Fortunately, he puts this into perspective: the political convicts were a small percentage and number.

Both authors cover the 1798 rebellion in Ireland and point out that it was not only the Catholics or the lower classes who participated. Again, O'Farrell's perception unravels some more complexity by emphasising that the murderous, violent Irish in early New South Wales (this name change was applicable in 1792 when Governor Captain Arthur Phillip returned to England as a result of ill health) was but a small minority which unfortunately attached itself to the more respectable and successful part of Irish society (p.25).

MacManus well describes the formation of the United Irishmen back in Ireland in 1791 and refers to one of the founders, Wolfe Tone, who wrote a pamphlet to unite the Catholics and the Dissenters. Tone pushed the vital points of a common interest and a common enemy, to rid themselves of their slavery and assert Ireland's independence and liberty (p.506). France and the United States had not long had their revolutions and were looked to for assistance.

England was determined to break the bond between the Catholics and Dissenters. The English Parliament controlled the Irish Parliament and the Convention Acts was passed which banned the Irish from having public meetings. What followed was extreme oppressive behaviour by the authorities and the forming of the Orange Order in 1795. Tone and his supporters fought back, which included Tone going to France for aid while in Ireland the formation of the United Irishmen began in earnest in 1796. This all leads to the uprising of 1798.

To counter this, Martial Law was brought in and was so savage that the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Ralph Abercrombie, resigned. This rebellion would be suppressed and no aid came from France. Tone was captured but declared in court 'the connection between Ireland and Great Britain as the curse of the Irish nation' (p.524).

Not long after, the Rising of 1803 was also another failure. Ironically, O'Farrell picks up the saga with a Michael Dwyer who was one of the leaders of '98 rebellion, surrendered after that 1803 rebellion and was sentenced to Australia where he became a settler. Dwyer was with a group of similar comrades at arms received land grants from Governor King, even though he did not like the Irish generally (p.29).

Governor King suspected rebellion from Dwyer and his colleagues. Governor Bligh, who succeeded King, went further by having Dwyer arrested on trumped up charges (not unlike what happened in Ireland in many other cases). Dwyer was banished to Norfolk Island and his friends to other areas. Dwyer personified the Irish Rebel when he was in Australia.

Interestingly, another '98 rebel, James Meehan, became a government surveyor and explorer in New South Wales. Again, O'Farrell's research points out that the 1798–1803 rebels were seen as heroes by their fellow Irish in Australia and people like Dwyer, and others, were exiles rather than prisoners, and the Governors feared them (pp. 30-31) and dispersed as many potential leaders as possible.

Sir Robert Peel, a politician back in England had similar thoughts: the 'educated' 'gentleman' convict was the worst and would create more problems. For many rebels, their conditions were not as bad as other convicts and several were successful as time progressed. Governor Macquarie, who succeeded Bligh, was more pacifying and those former rebels accepted the peace offering. Despite this, the colony was a prison and the authorities were harsh on the average prisoner, so much so, that there was the Castle Hill convict rising of 1804 that included English as well as Irish.

Ireland was quite dramatic in the 1840s and MacManus covers this well, from Daniel O'Connell's courageous battles in court, to a duel and being idolised by the Irish for his remarkable efforts and charisma on their behalf.

This was followed by Catholic Emancipation to the Young Ireland Movement, literally by a younger generation than O'Connell. Young Ireland had capable people and were patriots. They eventually split from O'Connell's influence which showed they had a mind of their own (pp. 590-91).

Ireland from 1845 to 1849 also experienced the Potato Famine which took a heavy toll on the population as a result of successive years of crop failure. This episode did not result in many Irish leaving for Australia; instead, that happened a few years later as a result of the gold rush period.

Europe, in 1848 experienced many revolutions: France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Hungary and others but their objectives differed, some slightly, some considerably. Italy and Germany longed for unification, Britain and France experienced resentment from the lower classes. Europe also had a potato famine; all the way to Poland. In Ireland, the spirit of Young Ireland was strong but, Britain was not sitting still either. Leaders of the movement in Ireland were arrested, including the editors of newspapers.

'Young Ireland' lacked food, arms and were no match for the British Empire. Some leaders were sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen's Land (later renamed Tasmania in 1855 after Dutch explorer Abel Tasman) as gentleman prisoners. Ireland once again was crushed by the British. Most of those Young Ireland leaders ultimately went back to Ireland or to America. One leader, Kevin O'Doherty, had an outstanding career as a physician in Australia and in Queensland, where he became a member of the Legislative Assembly.

O'Farrell summarises the situation thus: In Ireland, their traditional world was disappearing, causing concern about land, rents, and tithes to the Anglican Church leading to disturbances, crime and then transportation (p.35). One advantage Australia had, that the Irish soon realised when they arrived, was that of land grants and availability and paid labour.

Not all were farmers; eventually, they became policemen, railway workers etc. As rosy as this seems, farming was hard work in a climate of extremes, heat, drought and flood; to many, paid labour was preferred. Again, to those new Irish, to realise it, Australia relieved the stress of anarchy and violence so they brought up families; hardly thoughts for revolution.

Once more, this was not a perfect picture; the Catholic religion had attempts to wipe it out in favour of Protestantism. The Irish-Australians were stubborn and never easy to put down. The arrival from Ireland of Fathers Therry and Conolly helped pave the way for religious tolerance, virtually from the 1820s onwards (p.39), and Therry was a fighter.

One aspect of the Irish in Australia cannot be overlooked: the celebration of St Patrick's Day. During that period in the 1800s, they celebrated the day hard, much to the distress of Government officials.

From the 1830s, free immigrants were arriving into Australia and transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended in 1840. It was New South Wales who had received the majority of convicts. Many Irish in Australia went from being convicts to being free. Many became prosperous, but not without hardships and setbacks on the way and it was not home to many.

They became explorers, members of parliament, professional people and made up a substantial part of the Australian population and contributed in a multitude of areas. Sadly, Ireland from the 1790s to the 1840s experienced much hostility and infuriation from British dominance but, those who came to Australia, both convict and free, played a significant and important part to the building of a new country that had started as a prison.

|

GAELIC PHRASES OF THE MONTH

| PHRASE: |

bean mo chroi |

| PRONOUNCED: |

bann muh kree |

| MEANING: |

Woman of my heart |

| PHRASE: |

Ta tu go halainn |

| PRONOUNCED: |

taw two guh haul-inn |

| MEANING: |

You are beautiful |

| PHRASE: |

An bposfaidh tu me? |

| PRONOUNCED: |

on boes-igg two |

| MEANING: |

Will you marry me? |

View the Archive of Irish Phrases here:

http://www.ireland-information.com/irishphrases.htm

|

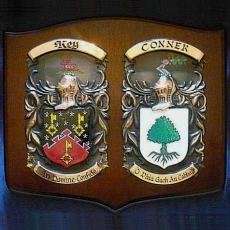

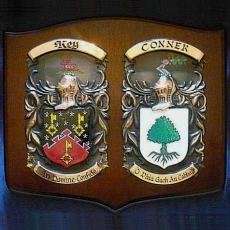

COMPETITION RESULT

The winner was: geraldinehiggins@ibbettmosely.co.uk

who will receive the following:

A Single Family Crest Print (US$24.99 value)

Send us an email to claim your print, and well done!

Remember that all subscribers to this newsletter are automatically entered into the competition every time.

|

I hope that you have enjoyed this issue.

by Michael Green,

Editor,

The Information about Ireland Site.

http://www.ireland-information.com

Contact us

Google+

(C) Copyright - The Information about Ireland Site, 2016

P.O. Box 9142, Blackrock, County Dublin, Ireland Tel: 353 1 2893860

|

|

|

MADE IN IRELAND!

MARVELOUS GIFTS FOR ANY OCCASION

FREE DELIVERY TO YOUR DOOR

Incredible Family Crest Plaques Made in Ireland

Family Crest Flags, Ireland Flags, Wedding Flags, Four-Province Flags, Erin Go Bragh Flags. Great Selection.

BIG REDUCTIONS!

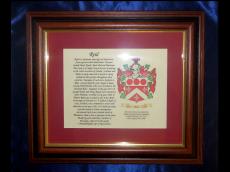

Stunning Family Crest

Signet and Seal Rings

DISCOUNTED FOR A LIMITED TIME

Elegant Cufflinks

Superior Framed

Family Crest Parchments

Gorgeous

Glistening Galway Crystal

'Your-Name' Old Irish Sign

NEW DESIGNS!

From US$34.99 - Free Delivery

New Designs available

on our Coffee Mugs

Personalized Licence Plate

Personalized First Name Plaque. Great for Kids!

New Designs available

on our Coffee Mugs

'Your-Name'

Polo & Tee Shirts

From US$69 Delivered

BIG REDUCTIONS!

Stunning Engraved Rings from Ireland with Irish Language Phrases.

Mo Anam Cara:

My Soul Mate

Gra Dilseacht Cairdeas:

Love, Loyalty, Friendship

Gra Go Deo:

Love Forever

Gra Geal Mo Chroi:

Bright Love of my Heart

|

SEE MORE GREAT OFFERS AND DISCOUNTS AT:

IRISHNATION.COM

FREE DELIVERY FOR A LIMITED TIME!

|

|

|

|