It is hard to overstate the influence that Michael Collins has had on Ireland.

It is just over a century since his death in his native Cork when he was ambushed and killed by his former comrades-in-arms, such is the appaling nature of a Civil War.

He fought in the GPO alongside Padraig Pearse in the Easter Rising of 1916; he ran a guerilla war against the British forces from 1919 that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921; and he led the new Irish Free State against his fellow Irish citizens, and Eamon deValera in particular, in the brutal Irish Civil War from 1922.

But his legacy in Ireland would live on.

Michael Collins was born near Rosscarbery in County Cork 1890. He attended

school and then worked as a local journalist (writing

sports reviews) before moving to London at the age of

15 to work for the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA).

In London Collins associated with the Irish community and

became keenly aware of the history of Irish nationalism.

He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1909. By

1915 he had risen though the ranks of the London branch

of the IRB and was aware of the increasing tension in

Dublin between the various factions of republicanism. He

returned home and helped in the recruitment that was

necessary before any uprising could be successful. He

also joined the Gaelic League, an organisation that

stressed the use of the Irish language as another means

of nationalistic expression.

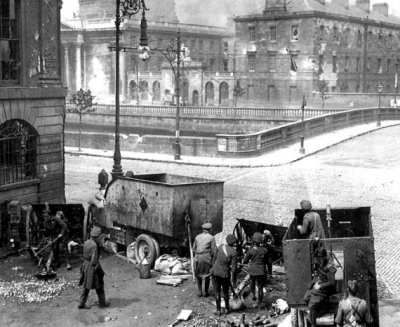

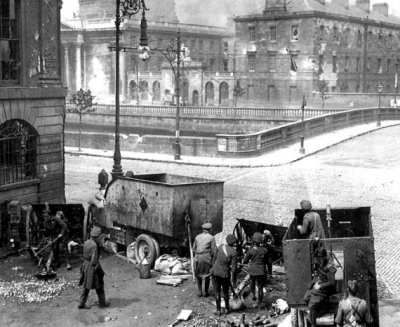

Despite the extreme unlikelihood of any success the Easter

Rising went ahead and resulted in the destruction of large

part of Dublin city centre as well as the execution of the

seven leaders of the revolt. This was the mistake by the

British that turned the tide in favour of the insurgents

for the first time. Public sympathy towards the executed

men increased so much that Collins, deValera and the

remaining leaders could see that nationalism was about to

peak in the country.

Collins was imprisoned in Frongoch internment camp where

his credentials as a leader were further recognised by his

captured comrades. After his release Collins quickly rose

to a high position in both Sinn Fein and the IRB and

started to organise a guerrilla war against the British.

He even managed to break deValera out of prison in England. The War

against the British continued on through 1920 and 1921

despite the introduction of the 'Black and Tans' - mercenary

soldiers introduced into Ireland by Churchill.

The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, eventually

compromised and offered a partition of Ireland and a

'Free State'. Collins and Arthur Griffith had been sent

to London to lead the Irish delegation. It is widely speculated that the wily deValera knew

that the ultimate aim - independence - was not attainable.

The result was Civil War. Brothers and sisters who had fought together against the British now turned on each other with a form of brutality that sometimes matched the excessive regime of even the British Empire.

The Civil war ended in 1923 when the brutal execution of so many of the IRA rank and file ground down their resistance with deValera leading calls for the war to end.

The Irish Free State would attempt to take its place among the nations of the world, with Irish Independence being formally declared in 1948.

It is impossible to know what Michael Collins might have achieved had he survived the Civil War. He surely would have become Taoiseach of Ireland and perhaps may have been able to address the issue of the partitioned six Counties in Ulster in his own unique way.

But what is clear is that he certainly knew of the risk he took in signing the Treaty with the British. This was the moment that Ulster became partitioned. He did so in the hope that the country would then have 'freedom to achieve freedom'.

His own words that were written in a letter dated 6 December 1921 after the signing of the Treaty proved remarkably prescient:

'Think — what I have got for Ireland?

Something which she has wanted these past 700 years.

Will anyone be satisfied at the bargain? Will anyone?

I tell you this: early this morning I signed my death warrant.'

And so he had.

He fought in the GPO alongside Padraig Pearse in the Easter Rising of 1916; he ran a guerilla war against the British forces from 1919 that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921; and he led the new Irish Free State against his fellow Irish citizens, and Eamon deValera in particular, in the brutal Irish Civil War from 1922.

He fought in the GPO alongside Padraig Pearse in the Easter Rising of 1916; he ran a guerilla war against the British forces from 1919 that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921; and he led the new Irish Free State against his fellow Irish citizens, and Eamon deValera in particular, in the brutal Irish Civil War from 1922.

He even managed to break deValera out of prison in England. The War

against the British continued on through 1920 and 1921

despite the introduction of the 'Black and Tans' - mercenary

soldiers introduced into Ireland by Churchill.

He even managed to break deValera out of prison in England. The War

against the British continued on through 1920 and 1921

despite the introduction of the 'Black and Tans' - mercenary

soldiers introduced into Ireland by Churchill.

The Civil war ended in 1923 when the brutal execution of so many of the IRA rank and file ground down their resistance with deValera leading calls for the war to end.

The Civil war ended in 1923 when the brutal execution of so many of the IRA rank and file ground down their resistance with deValera leading calls for the war to end.