The Vikings originated in Norway and Denmark and began their legendary raids during the eight century. The history of the Vikings in Ireland stretches

back to that time and culminates with

their defeat by Brian Boru at the Battle of

Clontarf in the year 1014.

The earliest recorded raid from Vikings out of

Norway was in the year 795 at Rathlin Island

off County Antrim.

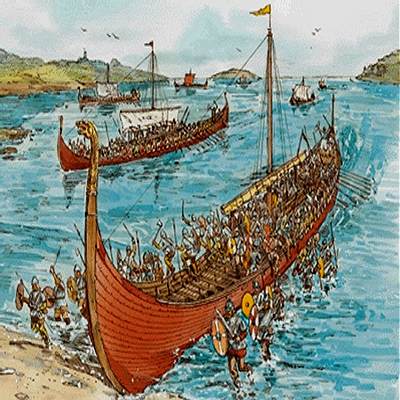

In the year 798 they raided the kingdom of Brega near the northern part of Dublin. These initial raids involved rapid landings, then plundering the local settlements and Monasteries before retreating back to the sea.

The Scottish isle of Iona

was also attacked in the same year. By the year 802

the raids had stretched around the western coast

as far as Skellig island and the ancient Monastery

there.

By the year 832 an intensification of the

attacks occurred with fleets of Viking ships

arriving at the Boyne, at Dublin and travelling

the Shannon estuary. They took supplies, riches

and slaves.

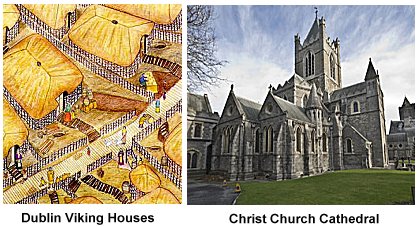

Early Viking leaders who raided Ireland include Saxolb in the year 837, Turges in the year in 845, and Agonn in the year 847. By the end of the ninth century the Vikings began to establish settlements known as 'longports' along the Irish coast. These were essentially coastal forts that protected the Viking boats. The earliest of these were at Linn Dúachaill (Annagassan) in County Louth and Duiblinn on the River Liffey, the forerunner of what would become Dublin, the capital city of Ireland.

The word Viking is taken from the Norse

word 'Vikingr' which means 'sea-rover' or 'pirate'.

Their longboats gave them an advantage that other

sea-faring peoples just could not match. Their

fierce attacks must have instilled terror into

the local population and especially at the

Monasteries where much of the wealth they craved

was located. It is no coincidence that the number

of high-towers built for protection in Ireland

greatly increased during this era.

By this time the Viking Chiefs Olaf and Ivar controlled the raids, some bringing as many as 1500 fighting men in many longboats - a veritable army.

The Irish chieftains now began their defence in

earnest since, as the Vikings had begun to make

semi-permanent settlements they had become a

much easier target. The Irish chieftain Máel

Seachnaill is recorded as having routed the

Vikings at Skreen in County Meath, putting over

700 of the invaders to death. Alliances between

the Vikings and the Irish chieftains became

commonplace as the presence of the norseman

became a political inevitability to be

acknowledged and dealt with.

By the year 849 invaders from Denmark had begun

to attack not only the Irish but also the more

established Vikings of Norwegian origin. By

853 'Olaf the White' had assumed control of

Dublin. He married the daughter of Áed Finnliath,

king of the northern Uí Néill. Decades of warfare

with some victories and some defeats for the

Vikings followed. In the year 902 the Irish

defeated the Vikings at Dublin.

A second wave of attacks began in the year 914

with a large fleet of Vikings ravaging Munster.

Over time the Irish fought back with some success.

The Dublin Vikings were attacked by the King of

Tara, the city sacked in the year 944.

The stage was set for a great showdown between

the two cultures with Brian Boru of Dál Cais

in County Clare being the spear-point of the

Irish attack. He had already defeated the Vikings

in Munster. His great rival was Máel Sechnaill II,

King of Tara. They reached an accord in the year

977 that Brian Boru would rule the southern part

of the country with Máel Sechnaill II ruling the

northern part.

They even collaborated on a raid

against the Dublin Vikings in the year 998. By

the year 1000 Brian Boru had put down a revolt by

the Dublin Vikings, defeating Sitric and

eventually forcing Máel Sechnaill II to

acknowledge him as the High King of all of Ireland.

The Leinster Vikings again revolted in the year

1012 but were once again defeated. They knew that

their time was limited so they sought help from

Sigurd, Earl of the Orkneys, who arrived in the

early part of 1014 to face the Irish.

The famous battle of Clontarf ensued with the

Irish squaring up to Sigurd, Brodar and Ospak

who were Vikings of the Isle of Man. With

Brian Boru, Brodar and Sigurd all killed in the

fierce battle that followed the Vikings were

eventually defeated, the battle entering the

pantheon of myth and legend of Viking history.

Estimates of the number of dead range from 6000

to over 12000, a huge number for warfare of

that time.

The Viking defeat at the battle of

Clontarf effectively signalled the end of Viking

rule in Dublin and thus throughout the country.

Long before this battle though the inevitable

integration of the two cultures had begun. The

invaders even assimilated the native Christian

religion, forming alliances, marrying and

eventually settling among the native Irish.

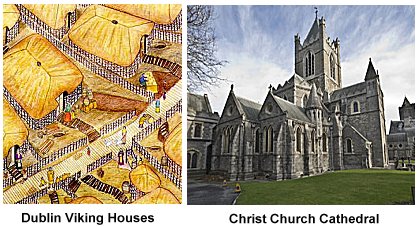

The legacy of the Vikings in Ireland is extensive.

The towns of Dubin, Cork, Wexford, Limerick and

Waterford that were initially founded by the

Vikings all developed into the major cities of

the modern era.

A full-scale invasion of the

island was never attempted as the Vikings had

matters in England and France to deal with.

Thus, despite the attacks, the native Irish

chieftains continued to prosper and make

treaties, war with each other and the Vikings,

sometimes allying with the 'norsemen' against

rival chieftains.

Coinage was first used in Ireland during the

Viking era further providing evidence of the

degree to which the Vikings changed from being

raiders to merchants and settlers. Dublin was

especially transformed by their presence, with

Christ Church Cathedral being built by Sitric.

The layout of the city centre today is much as

it was originally designed by the Vikings.

Further proof of their integration survives the centuries

through the use of surnames. Families of

McAuliffe (son of Olaf), McManus (son of Manus),

Doyle (the dark stranger or foreigner),

McLoughlin (son of Lochlainn) and McIvor (son of

Ivor) are just a few of the many 'Irish' names

that have deep roots within the Viking heritage.

The death of Brian Boru marked a period of further

fighting among the native Irish culminating with

the Anglo-Norman invasion in the year 1169 and

the beginning of a new period of warfare. It is

a tragic fact of Irish history that the various

chieftains and tribes remained so divided,

unwilling to create a central leader or kingship

capable of unifying opposition on the island to

the centuries of foreign invasion and hostility that were to follow.

In the year 798 they raided the kingdom of Brega near the northern part of Dublin. These initial raids involved rapid landings, then plundering the local settlements and Monasteries before retreating back to the sea.

In the year 798 they raided the kingdom of Brega near the northern part of Dublin. These initial raids involved rapid landings, then plundering the local settlements and Monasteries before retreating back to the sea.

They even collaborated on a raid

against the Dublin Vikings in the year 998. By

the year 1000 Brian Boru had put down a revolt by

the Dublin Vikings, defeating Sitric and

eventually forcing Máel Sechnaill II to

acknowledge him as the High King of all of Ireland.

They even collaborated on a raid

against the Dublin Vikings in the year 998. By

the year 1000 Brian Boru had put down a revolt by

the Dublin Vikings, defeating Sitric and

eventually forcing Máel Sechnaill II to

acknowledge him as the High King of all of Ireland.

Estimates of the number of dead range from 6000

to over 12000, a huge number for warfare of

that time. The Viking defeat at the battle of

Clontarf effectively signalled the end of Viking

rule in Dublin and thus throughout the country.

Estimates of the number of dead range from 6000

to over 12000, a huge number for warfare of

that time. The Viking defeat at the battle of

Clontarf effectively signalled the end of Viking

rule in Dublin and thus throughout the country.

A full-scale invasion of the

island was never attempted as the Vikings had

matters in England and France to deal with.

Thus, despite the attacks, the native Irish

chieftains continued to prosper and make

treaties, war with each other and the Vikings,

sometimes allying with the 'norsemen' against

rival chieftains.

A full-scale invasion of the

island was never attempted as the Vikings had

matters in England and France to deal with.

Thus, despite the attacks, the native Irish

chieftains continued to prosper and make

treaties, war with each other and the Vikings,

sometimes allying with the 'norsemen' against

rival chieftains.