IN THIS ISSUE

- News from Ireland

- Holding the Flashlight by Marie O'Byrne

- Tom Crean: Ireland's Unsung Hero by Bryce Babcock

- The Priest's Supper by T. Crofton Croker

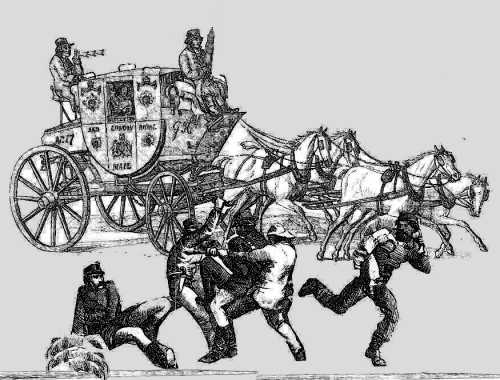

- Daring Robbery of the Belfast Mail-Coach - Irish Newspapers Revisited

- Gaelic Phrases of the Month

- Monthly Free Competition Result

Popular Articles from Recent Newsletters:

FOREWORD

Hello again from Ireland where the talk is all about the proposed change to the Irish Constitution (see the news article below). This month we feature a reminisce from Marie O'Byrne, an old tale from T. Crofton Croker and an article about the recently appreciated Irish Polar explorer from Kerry, Tom Crean.

If you have an article or story you would like to share then please do send it in.

Until next time,

Michael

P.S.

Please Do Forward this Newsletter to a

friend or relative. If you have a website or Facebook

page or Blog (or whatever!) then you can help

us out by putting a link on it to our website:

www.ireland-information.com

NEWS FROM IRELAND

BATTLE LINES BEING DRAWN IN ABORTION REFERENDUM

The decision by the Irish Government to hold a referendum to repeal the eight amendment to the Irish constitution has sparked the initial skirmishes in what is sure to be a bitter battle.

The eight amendment currently provides for...

'...the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.'

The amendment further copper-fastened the illegality of abortion in the country and effectively gave equal rights to life to the unborn and to the mother. The amendment was inserted into the Constitution after a referendum in 1983, (67% to 33%, on a 53% turnout of the electorate). Critics of the amendment point out that the new laws effectively put the life of the mother in balance against the life of an unborn foetus. Supporters argue that the law has saved countless lives, from their perspective.

The most recent campaign against the amendment began with the death of Savita Halapanavar in 2012, whose treatment by the Irish medical profession was reported around the world.

Despite the fact that successive Irish governments avoided the abortion issue completely, such was the consequent groundswell of support for a new referendum that the current government decided to offer the matter to the Irish people for their decision. Additionally (and significantly), individual T.D.'s (members of the Irish Parliament), will be free to vote (and even campaign) in whichever fashion they choose.

Indications are that the vote will be held in May of 2018. The campaign looks set to be bitter and divisive.

IRELAND HAS WORST HOSPITAL WAITING LISTS IN EUROPE

The crisis in the Irish healthcare system has been confirmed by statistics from the 'Euro Health Consumer Index of 2017'.

The index measures 35 countries across various categories and reports that Ireland is now ranked in 24th place overall.

In terms of waiting lists for operations and specialist appointments though, Ireland is at the very bottom of the list with the report commenting that the Irish performance in this area is 'abysmal'.

In terms of waiting lists for operations and specialist appointments though, Ireland is at the very bottom of the list with the report commenting that the Irish performance in this area is 'abysmal'.

The report has also confirmed that there is no correlation between accessibility to healthcare and the amount of money spent. This is a viewpoint that has been continually put forward in recent years by many Irish commentators and is borne out by the massive amounts of funding that the Irish healthcare system continues to receive. Other EU countries have been able to significantly improve their healthcare without ploughing billions of extra euro into the system.

The report notes:

'It is inherently cheaper to run a healthcare system without waiting lists than having

waiting lists! Contrary to popular belief, not least among healthcare politicians, waiting

lists do not save money – they cost money!

....If countries with limited means, (Montenegro, Slovakia), can achieve virtual absence of waiting lists – what excuse

can there be for countries such as Ireland, the UK, Sweden or Norway to keep having waiting list problems?'

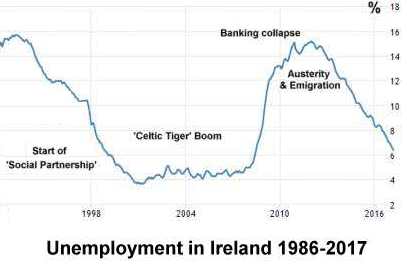

UNEMPLOYMENT RATE DOWN AGAIN

The rate of unemployment in Ireland has again fallen and is currently at 6.1%, compared to 7.4% in January 2017 and over 15% at the depths of the economic crash in 2012. This is a remarkable reversal as the economy heads towards 'full employment' (generally regarded as being a 4% unemployment rate). The rate of unemployment in Ireland has again fallen and is currently at 6.1%, compared to 7.4% in January 2017 and over 15% at the depths of the economic crash in 2012. This is a remarkable reversal as the economy heads towards 'full employment' (generally regarded as being a 4% unemployment rate).

Critics of the current economic policies of the Fine Gael government argue that these figures are skewed given the huge numbers who have emigrated from Ireland over the last decade.

CHILDREN OF PARENTS WHO GRADUATED ARE MORE LIKELY TO SUCCEED

While most people agree that a better education will at the very least provide greater opportunities for their children in later life what is less well defined is the actual 'hereditary' link regarding educational outcome through the generations.

The recent 'Eurostudent VI' report on the social and living conditions of 20,000 third-level students in Ireland in 2016 found that in homes where a parent had achieved 'Junior Cert' level (approx age 15 to 16 years) then 69% of children progressed to third level education (University, College or Professional courses). In homes where a parent had studied beyond 'Leaving Cert' level (approx 17 to 18 years), then 93% of children progressed to third level education.

So these numbers clearly establish the link between a parents' past experience and their expectations that they have for their child, with the likelihood that their child will progress educationally.

Ireland continues to have one of the highest levels of third-level enrollment by students in Europe, at approximately 60%.

|

KEEP THIS NEWSLETTER ALIVE!

FIND YOUR NAME IN OUR

GALLERY OF IRISH COATS OF ARMS

|

HOLDING THE FLASHLIGHT

by Marie O'Byrne

Through the eyes of a child, the night rain seemed harsher, colder and somehow more threatening than the softer showers of the day. I was about ten years old and my job was to hold the flashlight for my mother while she hung out the clothes in the back garden. After a long day of housework she usually only got around to hanging out the washing in the late dark evenings after supper.

It was pitch black down there at nighttime, surrounded by tall trees and thick hedge. We could see the light from the kitchen window in the distance but it was too far away from us to be of any benefit. I had to shine the light down on the big basins in the grass so my mother could see what clothes she picked out and then shine it up on the clothes line.

'Hold it steady, Marie. Shine it up on the clothes line and be still, good girl,' said my mother as she stretched her arms up and searched with her cold hands along the narrow line for more clothes pegs. It was raining as usual - my mother wore her old navy blue raincoat and head scarf. I stood close beside her, an umbrella in one hand and the flashlight in the other. Dozens of wet socks, and underwear, trousers, shirts and cardigans, there seemed to be no end to all the wet clothes in those big plastic basins and we hadn't even taken the towels and sheets out yet.

My mother was the only person I ever knew who hung the washing out in the rain. She believed that the cold fresh rain would give the clothes a good rinsing during the night, but more importantly, it also relieved her from the daunting task of having to rinse out all the clothes in the little sink. A brilliant idea on her part I think. Necessity is the mother of invention they say.

With thirteen people in our family and no washing machine, it was understandable that my mother always seemed to be in a constant state of laundry processing. It was a familiar sight to see buckets and basins full to the brim of socks and underwear soaking in Ariel by the kitchen door or on the back steps while the towels and sheets soaked in the sink and in the old metal bath tub. She would only stop this daily, never ending job, to run and stir the stew cooking on top of the range or to clean and sweep the floors of the cottage or tend to the children. Of course, if a neighbor showed up at the door she would stop all her work and make a cup of tea and sit for a quick chat. She always made time for people who dropped by, making them feel welcome and important even though she knew that this set her work schedule back and that she would end up, yet again, having to hang out all the clothes in the dark.

I was afraid of the dark, being outside in the back garden at nighttime scared the wits out of me. The grunting and rustling sounds from the old hedgehog that lived in the bushes only added to my fear. When I reflect back, I think my mother was also afraid of the dark as she would always sing a song to me as she hung out the clothes, 'Que Sera Sera' was her favorite and I sang along with her, dancing around in the wet grass to keep warm, my eyes darting from tree to tree, scanning the blackness and wishing I could just run back to the warmth of the cottage. The sweet smell of the burning peat and wood wafting in the damp air taunted and beckoned me inside.

'Hurry up, Ma,' I whispered under my breath. Her cold hands continued to search in the darkness for the next wooden peg and on and on down the line she went - bending, reaching and pulling - bending reaching and pulling.

Finally, with the last of the clothes hung out, my mother pushed the two loaded lines up higher into the black night sky using the two long wooden poles for support. My father had made the poles from tall ash trees that he had carefully selected up in the woods.

She would turn to me as she gathered up the basins and say, 'We're all done now love, lets pray for a good day tomorrow!' A good day in my mother's eyes was when the rain died down during the night and the cold sea breeze coming in from the East picked up quickly. She loved to see her clothes flying high in the forceful wind, flapping and folding into each other. She knew that the drier the clothes were coming in from outside, the less time they had to spend 'airing' on the little clothes line that hung under the mantelpiece of the old range, or on the backs of the kitchen chairs. With the old range being the only source of heat in the cottage, she didn't want to have it covered and cluttered with clothes when we all came in from school cold and tired. However, all the clothes had to be 'aired' by the fire before she put them away in the clothes press.

Growing up in Ireland, during the 1960's, was very tough, it was a time of great hardship with few material comforts. I didn't know anyone on our road who owned a washing machine or a tumble dryer. Even though we lacked the material things we were rich with an abundance of love and family unity and we were always assured of our mothers loving presence and support. She was full of kindness, joy and laughter and I am very thankful for all the wonderful memories.

With such a large family, everyone had a job to do, the boys did most of the outdoor chores and we six girl's did the inside jobs, we all helped each other out, whether it was setting the table, peeling the potatoes or washing the dishes, it was just an everyday part of life growing up in a large family.

Looking back, I wouldn't trade one of those dark rainy nights with my mother for anything in the world.

Marie O' Byrne

http://www.marieobyrne.com

|

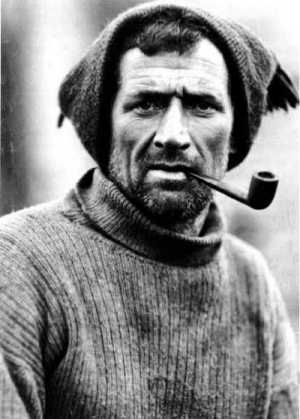

TOM CREAN: IRELAND'S UNSUNG HERO

by Bryce Babcock

'He ran away to join the navy, when he was just fifteen, A farmer's son from Annascaul, the tough and brave Tom Crean.'

So begins 'The Ballad of Tom Crean' one of Ireland's, and the world's, true unsung heroes.

One of 10 children born to Patrick and Catharine Crean, Tom had left school at the age of 12, to lend much needed help on his father's farm near the little town of Annascaul on the Dingle Peninsula in southwestern part of Ireland, in County Kerry.

It was in 1892 that, after an argument with his farmer father, fifteen year old Tom Crean ran away from home and after lying about his age, he enlisted in Britain's Royal Navy.

By his 18th birthday he was rated as an 'Ordinary Seaman', and had advanced to Petty Officer 2nd Class by 1899.

In December 1901, on board a ship of the Royal Navy's New Zealand Squadron, he was helping to prepare Robert Falcon Scott's ship 'Discovery', when a crewman of Scott's ship deserted. A replacement was required!

Crean volunteered, was accepted, and so became a member of Scott's Discovery Expedition.

Crean's attitude and work ethic led Scott to request the young Irishman to join him on his Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica. Crean duly obliged.

Early on in the expedition he saved the lives of two members of the team when the three camped on unstable sea ice. The ice broke up during the night, leaving the men adrift. Crean leapt from flow to flow until he reached stable ice and was able to bring help.

In 1912 Tom Crean was a member of Scott's party that attempted to reach the South Pole. As they neared the Pole, Scott ordered Crean, William Lashly and Edward 'Teddy' Evans to return to the base while he and four others made the final dash for the Pole. They reached the South pole only to discover that the Norwegian party led by Roald Amundsen had reached their target ahead of them.

Captain Scott's South Polar Party in 1911

Captain Scott's South Polar Party in 1911

Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers, PO Evans, Lt Evans, Lashly, Crean

On the return trip all of Scott's party perished.

Meantime, Crean, Lashly and Teddy Evans were making their way back to the base at Hut Point. Evans, suffering from scurvy, collapsed and could go no farther. Crean and Lashly, dragging a semi-conscious Evans on a sledge got within 35 miles of the base at Hut Point.

Lashly could go no farther, but agreed to care for the now comatose Evans while Crean tried to reach Hut Point on foot.

With nothing for sustenance but three ship's biscuits and two small pieces of chocolate, Tom Crean walked the 35 miles to the Hut Point encampment and sent back help. He covered the 35 miles in 18 hours of steady walking, reaching the base just 30 minutes ahead of a raging blizzard which probably would have killed him.

The rescue party reached Lashly and Evans and brought them both in safely. Both Crean and Lashly were awarded the Albert Medal, one of the highest British awards for gallantry, for saving Evans' life while Crean was promoted to Chief Petty Officer.

In November, 1912, Tom Crean was a member of the eleven-man search party that found the bodies of Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Wilson and Henry 'Birdie' Bowers. They had spotted a cairn of drifted snow that covered a tent containing the 3 bodies. The bodies of 'Taffy' Evans and 'Titus' Oates were never found. Unable to continue, both had walked away from the camp in vain attempts to save Scott, Wilson and Bowers.

The other great British polar explorer of the time, Ernest Shackleton, knew Crean well and also knew of his feats with Scott's expedition. Shackleton welcomed Crean to his Transantarctic Expedition of 1914 when he hoped to cross the Antarctic Continent.

One of Crean's responsibilities was to take charge of the dog-handling teams. The expedition's ship Endurance became trapped in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea. After drifting in the ice for months the pack ice finally crushed the ship which sank on November 21, 1915. Three lifeboats were saved and the stranded men set out to drag them across the ice to open water which they reached on April 9.

Shackleton and his men then took to the lifeboats and reached rocky, uninhabited Elephant Island after a further five days. Tom Crean piloted one of the three boats.

Rather than wait for a rescue ship that might never come, Shackleton decided to strengthen the largest of the lifeboats, 'The James Caird', and sail it to South Georgia Island, the nearest place with a known permanent settlement, a whaling station.

Shackleton would take five men, including Tom Crean, and try to sail 'The James Caird' more than eight hundred miles to South Georgia Island through some of the roughest seas in the world.

Frank Wild was left in command of the rest of the men who would stay behind, sheltered by the two remaining upturned boats and subsisting on a diet consisting largely of seals and penguins.

Described by polar historian Caroline Alexander as 'one of the most extraordinary feats of seamanship and navigation in recorded history', the voyage of 'The James Caird' took seventeen days through gales and heavy snow squalls in treacherous seas.

Finally they reached the south coast of South Georgia Island, mainly thanks to the navigational skills of Frank Worsley, Captain of 'The Endurance' and one of the six men on board. But the south coast of the island was uninhabited.

The whaling station of Stromness was on the north coast.

In landing, the rudder of 'The James Caird' had been damaged beyond repair and Worsley knew that if they tried to sail around the island without a rudder, they would be swept out to sea.

The only option was to cross the thirty miles of mountains between them and the whaling station on foot, a feat that had never been tried, let alone accomplished.

Three of the men were unfit to make the attempt, so it was up to Shackleton, Worsley and Tom Crean.

The three made the thirty miles in thirty-six hours! It was the first recorded crossing of the island and was made without any mountaineering equipment other than one carpenter's adze, a fifty foot length of alpine rope and some screws hammered through the soles of their boots to serve as crampons.

Somehow they made it, and quickly organized a boat to pick up the three men on the other side of the island. Still, it took three months and four attempts by ship to rescue the men left behind on Elephant Island. Miraculously there had not been a single fatality among the crew of 'The Endurance'.

For his bravery Tom Crean was awarded his third 'Polar Medal'. He returned to Annascaul, married Ellen Herlihy and fathered three daughters.

Tom and Ellen built and opened a pub in Annascaul, naming it The South Pole Inn.

In 1920 Shackleton asked Crean to join him on another Antarctic expedition, but Crean, married, a father, and about to open his Pub, declined. Tragically Crean's second daughter, Kate, died when she was just 4 years old.

In 1938 Crean suffered a ruptured appendix which was a very serious condition at the time. There was no surgeon immediately available, infection set in and he died on 27 July, 1938, shortly after his sixty-first birthday.

Tom Crean was a very humble, modest man. He never spoke of his experiences with Shackleton and Scott to his family. His daughter, Eileen said 'he put his medals and sword in a box, put them away and that was that.'

The two surviving daughters, Eileen and Mary, continued to operate the South Pole Inn for many years and after his death decorated it with some of their father's memorabilia that can be seen there today.

The walls of the downstairs rooms are covered with photographs from Tom Crean's days in Antarctica, and a statue of Crean stands adjacent to the pub.

|

THE PRIEST'S SUPPER

T. Crofton Croker

It is said by those who ought to understand such things, that the good people, or the fairies, are some of the angels who were turned out of heaven, and who landed on their feet in this world, while the rest of their companions, who had more sin to sink them, went down farther to a worse place.

Be this as it may, there was a merry troop of the fairies, dancing and playing all manner of wild pranks, on a bright moonlight evening towards the end of September. The scene of their merriment was not far distant from Inchegeela, in the west of the county Cork - a poor village, although it had a barrack for soldiers.

But great mountains and barren rocks, like those round about it, are enough to strike poverty into any place. However as the fairies can have everything they want for wishing, poverty does not trouble them much, and all their care is to seek out unfrequented nooks and places where it is not likely any one will come to spoil their sport.

On a nice green sod by the river's side were the little fellows dancing in a ring as gaily as may be, with their red caps wagging about at every bound in the moonshine, and so light were these bounds that the lobs of dew, although they trembled under their feet, were not disturbed by their capering. Thus did they carry on their gambols, spinning round and round, and twirling and bobbing and diving, and going through all manner of figures, until one of them chirped out,

'Cease, cease, with your drumming,

Here's an end to our mumming.

By my smell

I can tell

A priest this way is coming!'

And away every one of the fairies scampered off as hard as they could, concealing themselves under the green leaves of the lusmore, where, if their little red caps should happen to peep out, they would only look like its crimson bells; and more hid themselves at the shady side of stones and brambles, and others under the bank of the river, and in holes and crannies of one kind or another.

The fairy speaker was not mistaken; for along the road, which was within view of the river, came Father Horrigan on his pony, thinking to himself that as it was so late he would make an end of his journey at the first cabin he came to. According to his determination, he stopped at the dwelling of Dermod Leary, lifted the latch, and entered with 'My blessing on all here'.

I need not say that Father Harrigan was a welcome guest wherever he went, for no man was more pious or better beloved in the country. Now it was a great trouble to Dermod that he had nothing to offer his reverence for supper as a relish to the potatoes, which 'the old woman', for so Dermod called his wife, though she was not much past twenty, had down boiling in a pot over the fire; he thought of the net which he had set in the river, but as it had been there only a short time, the chances were against his finding a fish in it.

'No matter'" thought Dermod, 'there can be no harm in stepping down to try; and maybe, as I want fish for the priest's supper, that one will be there before me.'

Down to the river-side went Dermod, and he found in the net as fine a salmon as ever jumped in the bright waters of 'the spreading Lee' but as he was going to take it out, the net was pulled from him, he could not tell how or by whom, and away got the salmon, and went swimming along with the current as gaily as if nothing had happened.

Dermod looked sorrowfully at the wake which the fish had left upon the water, shining like a line of silver in the moonlight, and then, with an angry motion of his right hand, and a stamp of his foot, gave vent to his feelings by muttering, "May bitter bad luck attend you night and day for a blackguard schemer of a salmon, wherever you go! You ought to be ashamed of yourself, if there's any shame in you, to give me the slip after this fashion! And I'm clear in my own mind you'll come to no good, for some kind of evil thing or other helped you---did I not feel it pull the net against me as strong as the devil himself?"

'That's not true for you' said one of the little fairies who had scampered off at the approach of the priest, coming up to Dermod Leary with a whole throng of companions at his heels: 'there was only a dozen and a half of us pulling against you.'

Dermod gazed on the tiny speaker with wonder, who continued, 'Make yourself noways uneasy about the priest's supper; for if you will go back and ask him one question from us, there will be as fine a supper as ever was put on a table spread out before him in less than no time.'

'I'll have nothing at all to do with you' replied Dermod in a tone of determination; and after a pause he added, 'I'm much obliged to you for your offer, sir, but I know better than to sell myself to you, or the like of you, for a supper; and more than that, I know Father Harrigan has more regard for my soul than to wish me to pledge it for ever, out of regard to anything you could put before him - so there's an end of the matter.'

The little speaker, with a pertinacity not to be repulsed by Dermod's manner, continued, 'Will you ask the priest one civil question for us?'

Dermod considered for some time, and he was right in doing so, but he thought that no one could come to harm out of asking a civil question. 'I see no objection to do that same, gentlemen,' said Dermod; 'but I will have nothing in life to do with your supper -mind that.'

'Then' said the little speaking fairy, whilst the rest came crowding after him from all parts, 'go and ask Father Horrigan to tell us whether our souls will be saved at the last day, like the souls of good Christians; and if you wish us well, bring back word what he says without delay.'

Away went Dermod to his cabin, where he found the potatoes thrown out on the table, and his good woman handing the biggest of them all, a beautiful laughing red apple, smoking like a hard-ridden horse on a frosty night, over to Father Horrigan.

'Please your reverence,' said Dermod, after some hesitation, 'may I make bold to ask your honour one question?'

'What may that be?' said Father Horrigan.

'Why, then, begging your reverence's pardon for my freedom, it is, If the souls of the good people are to be saved at the last day?'

'Who bid you ask me that question, Leary?" said the priest, fixing his eyes upon him very sternly, which Dermod could not stand before at all.

'I tell no lies about the matter, and nothing in life but the truth," said Dermod. 'It was the good people themselves who sent me to ask the question, and there they are in thousands down on the bank of the river, waiting for me to go back with the answer.'

'Go back by all means,' said the priest, 'and tell them, if they want to know, to come here to me themselves, and I'll answer that or any other question they are pleased to ask with the greatest pleasure in life.'

Dermod accordingly returned to the fairies, who came swarming round about him to hear what the priest had said in reply; and Dermod spoke out among them like a bold man as he was: but when they heard that they must go to the priest, away they fled, some here and more there, and some this way and more that, whisking by poor Dermod so fast and in such numbers that he was quite bewildered.

When he came to himself, which was not for a long time, back he went to his cabin, and ate his dry potatoes along with Father Horrigan, who made quite light of the thing; but Dermod could not help thinking it a mighty hard case that his reverence, whose words had the power to banish the fairies at such a rate, should have no sort of relish to his supper, and that the fine salmon he had in the net should have been got away from him in such a manner.

|

HELP KEEP THIS NEWSLETTER ALIVE!

|

IRISH NEWSPAPERS REVISITED

DARING TRAIN ROBBERY

Connaught Journal, Galway, Ireland. January 2, 1823.

DARING TRAIN ROBBERY

Connaught Journal, Galway, Ireland. January 2, 1823.

ROBBERY OF THE BELFAST MAIL

On Friday night the Belfast Mail, when on its way from Dublin, was stopped

on the Ashbourne road, beyond Duleek, and within 7 1/2 miles of Drogheda,

near to an old burying-place.

The banditti placed across the road several

carts, ladders, and wooden gates and when the coach arrived at the prepared

spot, there was a cry to surrender, which the guards answered by a

volley-this was returned by a fire from behind the hedges each side of the

road which wounded both guards; one of them, named Lewis Byrne, received a

ball in his left groin, another in his left thigh, and one in his right

side.

The other guard, named Gregory Farrell, received a passing ball across

his forehead. The robbers (about fifteen in number) then surrounded the

coach, and took the fire-arms, consisting of three double-barelled short

guns, three double-barrelled brass blunderbusses, and four pistols; they

broke open the lockers, and took the Mail bag for Drogheda, and several

other parcels.

There was a sum of 10,000 in whole bank notes in part of the

coach, which fortunately escaped their search. The knowledge of this sum

(which was for the Belfast bank) being in the coach, it is thought

occassioned the attack.

The robbers were two hours and a half arranging

their plans, before the arrival of the coach. They went around to the

neighbouring cottages, and after shutting up every person in their place,

and sending them in from their out-houses, they left an armed sentinel at

the doors to prevent their coming out.

The occasion of their getting

possession of the Drogheda Mail bag was owing to the guard having it

uppermost, in order to hand out to the Post-office when passing through.

There were four inside and three outside passengers, all of whom were

searched and robbed of their watches and money-they also took the contents

of their trunks-there were five watches and about 100 taken from the

passengers, but they had no great booty in the Drogheda bag.

The guard, Lewis Byrne, was removed to Drogheda and lies dangerously ill. There were

several shots through the body of the coach, but happily neither the

coachman nor passengers received the least injury.

The coach afterwards proceeded to Belfast.

|

HELP KEEP THIS NEWSLETTER ALIVE!

|

GAELIC PHRASES OF THE MONTH

| PHRASE: |

Thóg mé. Níor thóg mé. |

| PRONOUNCED: |

hoeg may. neer hoeg may. |

| MEANING: |

I took. I didn't take. |

| PHRASE: |

Chuir mé. Níor chuir mé |

| PRONOUNCED: |

qwirr may. neer qwirr may. |

| MEANING: |

I put. Ididn't put. |

| PHRASE: |

Thug mé. Níor thug mé |

| PRONOUNCED: |

hug may. neer hug may. |

| MEANING: |

I gave. I didn't give. |

View the Archive of Irish Phrases here:

http://www.ireland-information.com/irishphrases.htm

|

COMPETITION RESULT

The winner was: Tom.buckley@lusfiber.net

who will receive the following:

A Single Family Crest Print (usually US$24.99)

Send us an email to claim your print, and well done!

Remember that all subscribers to this newsletter are automatically entered into the competition every time.

I hope that you have enjoyed this issue!

by Michael Green,

Editor,

The Information about Ireland Site.

http://www.ireland-information.com

Contact us

Google+

(C) Copyright - The Information about Ireland Site, 2018. P.O. Box 9142, Blackrock, County Dublin, Ireland Tel: 353 1 2893860

|

All Content is Copyright (C), 2018 Ireland-Information.com

unsubscribe/disconnect from Ireland here

The Information about Ireland Site

(C) Copyright - IrelandInformation.com, 1998-2017

|