During the 1970’s and 1980’s in Ireland the annual remembrance of those tens of thousands of Irish who gave their lives in the Great War was met with a kind of muted national indifference.

Certainly there was laying of wreaths and some elderly people would wear a poppy (before the poppy symbolism was hijacked by the British establishment in an effort to promote their own particular brand of nationalism).

But once the brief RTE television news report had been played the Irish people continued on without much acknowledgement of the anniversary, with younger people especially indifferent to what seemed like a quaint pre-independence ritual.

After all, the ‘real’ heroes of the Irish republic were the men of 1916, Pearse and Connolly, the men and women who had fought the War of Independence and the subsequent Civil War, deValera and Collins, plunging Ireland into a scarring divide that would hold the economically bankrupt country back for generations to come.

The Civil War divide still remains in Ireland, but it is very much on its last knees. At last a left-wing Labour movement has emerged (although not necessarily via the Labour Party). Incredibly that may even necessitate a union of the two former political enemies. Even twenty years ago this would have seemed like a fanciful proposition. It was just impossible to conceive that Fianna Fail and Fine Gael would form a coalition together. But now the electoral arithmetic makes that outcome a very real possibility.

What of the 50,000 who perished in the war? What is their legacy following the march of time.

Finally it seems that their sacrifice is being realized. It was in 1966 that Sean Lemass, the Irish Taoiseach who is credited with dragging the country into the developed economic world remarked:

‘In later years, it was common – and I also was guilty in this respect – to question the motives of those men who joined the new British armies formed at the outbreak of the war, but it must, in their honour and in fairness to their memory, be said that they were motivated by the highest purpose, and died in their tens of thousands in Flanders believing they were giving their lives in the cause of human liberty everywhere, not excluding Ireland.’

It would be nearly a half century though before an admiration, or at least an acknowledgement, of those Irish troops who joined the British army could co-exist with a similar admiration (even worship in many cases) of those men and women who had fought in the cause of Irish freedom in the ruins of the GPO on Easter Sunday in 1916, or in the fields of Ireland against the Black and Tans in 1921.

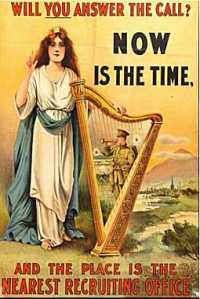

Why did they do it? Why did the Irish volunteer for the British Army?

The motivation of soldiers in any age, including today, who are often impervious to any criticism, such is the level of bombast in certain places, is rarely easy to grasp.

Many initially volunteered for the money. This was the Ireland of ‘Strumpet City’ and ‘The Lockout’. Jobs were very hard to find and when found, paid poorly. Poverty, especially in the main Irish cities of Dublin and Cork was extraordinary, even by modern day standards.

Today there are various definitions of poverty, the most often used in Ireland is that anyone with an income of 60% of the average national wage is ‘in poverty’. In the decade leading up to the great war such a definition would have been much more relevant. In modern Ireland the lack of a TV satellite dish is regarded as a symbol of poverty. Everything is relative.

Most however, joined to represent their country and to fight for freedom. When the all but forgotten Irish nationalist John Redmond encouraged and even demanded that his Irish followers enlist in the British army to fight the German menace he did so in the hope that the service of the Irish would be remembered and rewarded. It is easy to look back now and lament at how naive he must have been.

Francis Ledwidge was an Irish volunteer who was to die in preparation of the Third battle of Ypres in 1917:

‘I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy of civilisation and I would not have her say that she defended us while we did nothing but pass resolutions.’

The stage was set in Ireland for another dramatic failure, as that what the Easter Rising was from a military standing. But the British over-reacted, executed the Irish rebel leaders. Their martyrdom ensured that the die was cast and the Irish journey to independence was unstoppable.

What might those Irish trapped in the blood-filled trenches of Belgium and France have thought now?

Francis Ledwidge again:

‘If someone were to tell me now that the Germans were coming in over our back wall, I wouldn’t lift a finger to stop them. They could come!’

Poelcapelle Cemetery in Flanders is the final resting place of Private John Condon who hailed from Waterford and was known as the ‘Boy Soldier’. He had worked as a bottler in Sullivan’s Bottling Stores in Waterford before, aged 13 years, he lied his way into the British army. He is recorded as the youngest military casualty of the first World War.

He died at the second battle of Ypres in May 1915, killed in action at Bellevarde Ridge on a day when ‘a strange greenish mist crept across from the enemy position, to attack the eyes and throat and burn out the lungs.’

So many Irish soldiers returned to their country with damage to their lungs from the poison they had breathed, many to suffer for decades with their injuries.

As many as 206,000 Irish soldiers served in the British army during the first world war.

Over 50,000 perished.

On this Remembrance Day nearly a century later should we not ask: Is Private John Condon any less of a martyr in the cause of Irish freedom than Pearse or Connolly?

Michael Green is Manager of The Information about Ireland Site

Michael Green is Manager of The Information about Ireland Site